Inside Boston'S 1976 Combat Zone: The Glamour And Reality Of Strippers And Showgirls

A Glimpse into Boston's Combat Zone

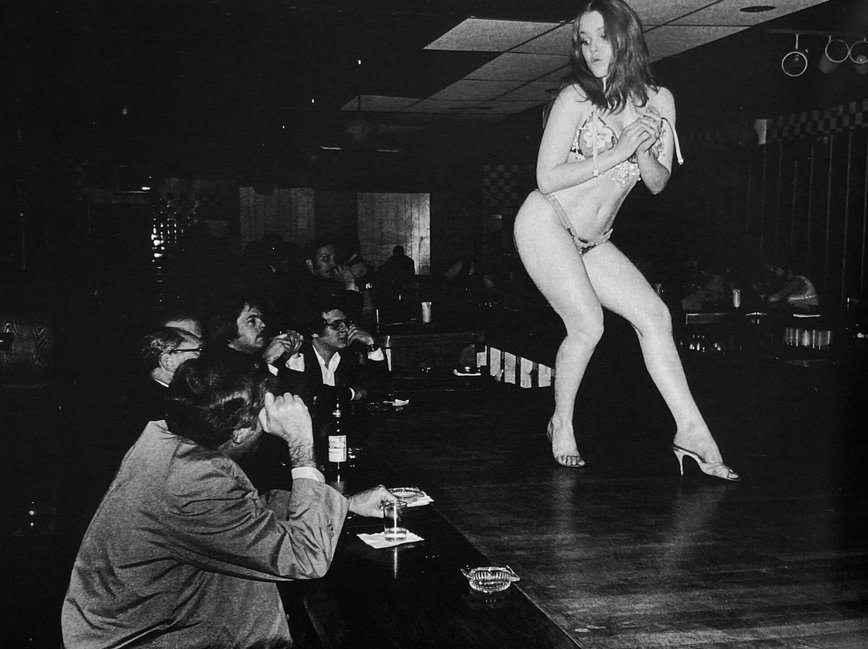

In the lively streets of 1970s Boston, the Combat Zone stood out as a hub of nightlife, intrigue, and a curious blend of glamour and grit. Once a bustling Navy port, this area near Washington Street became synonymous with its bars and strip clubs, attracting a mix of characters seeking entertainment and escape. Roswell Angier, a photographer renowned for his compassionate eye, captured this vibrant world in his seminal work, A Kind of Life: Conversations in the Combat Zone (1976).

Angier's project, reminiscent of EJ Bellocq’s work in New Orleans' Storyville, took an intimate look at the inhabitants of the Combat Zone. His portraits and interviews with showgirls, strippers, and other denizens reveal a hidden layer of humanity beneath the flash and façade of the stage. Through his lens, Angier introduced us to the likes of Jeri, Deirdre, and Satan’s Angel, each with a story as compelling as their stage names suggest.

The Stories Behind the Spotlight

These performers, while dazzling audiences with their crafted personas, navigated a challenging world. Angier’s conversations unveil personal tales of resilience and aspiration. As one performer at the Two O’Clock Club conveyed, there was a stark difference between the raunchy stereotypes and the real women behind them. "There’s this one girl, even bigger than Chesty Morgan. Her breasts are bigger than watermelons. She has to harness them up," she remarked, candidly discussing the physical and emotional demands of their craft.

“It seems like what has been done in the way of magazine articles and stuff like that has to do with the really raunchy girls," a stripper shared, highlighting the often-misunderstood lives of these women.

Beyond the stereotypes, Angier documented the camaraderie, the dreams, and the unyielding spirit of survival. His subjects shared their world candidly, revealing their struggles with silicone enhancements and the societal pressures they faced. As Angier noted, each had a unique story that went far beyond their time in the spotlight.

The Enduring Mystique of Showgirls

Showgirls like Faye Harlowe epitomized a different kind of allure – one marked by elegance and a keen sense of "class." As Angier's work illustrates, these women crafted their own armor against the vulnerabilities of their profession. Their aspirations, while not always apparent on stage, were grounded in dreams of stability and success beyond the club.

Through Angier’s lens, the Combat Zone becomes more than a place of fleeting pleasures; it’s shown as a community of individuals living day-to-day, each with their own battles and dreams. These stories, captured in A Kind of Life, resonate with the enduring struggle for dignity and identity in a world that often reduces them to mere spectacle.